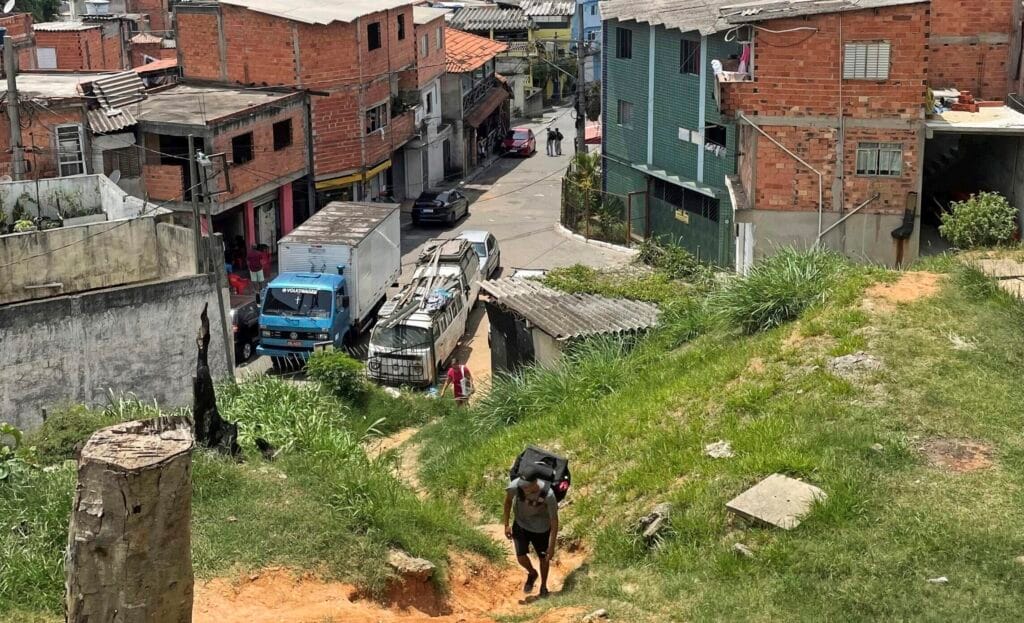

The concrete wall surrounding the São Paulo F1 circuit marks the boundary between two worlds. The ostentatious nature of Formula 1 contrasts starkly with the bitter poverty of the residents in the adjacent favela. A greater contrast is hardly imaginable. This report explores life and survival on the other side of the wall.

Is it a wise idea to take an evening stroll through the Interlagos favela? With a serious look, she sizes up her visitor from the Netherlands from head to toe. Dark hair, brown eyes, jeans, blue T-shirt. Then, after a brief contemplation: “You could pass for a Brazilian. But one thing: keep your mouth shut! If they hear that you’re not a local, you’re taking a serious risk.”

The Autódromo José Carlos Pace in São Paulo is one of the most storied circuits on the F1 calendar. It’s known for its history and challenging layout, but also for its location, right next to one of the dozens of slums in the Brazilian metropolis of about 25 million inhabitants. Every year, the arrival of the billion-dollar spectacle that is Formula 1 creates a stark contrast. Racing on one side of the wall, survival on the other.

Working sewage, running water, electricity, and a leak-free roof are not a given for every resident of Interlagos. According to recent figures, about 15,000 people live in the slum next to the circuit. In total, São Paulo has about three million people living in dozens of favelas. Interlagos is one of the smaller ones, but probably the most famous, thanks to Formula 1. The residents are generally proud and happy about this. Simply because it brings in money.

In Interlagos too, some have it better than others. Manoel Andrade (22) and Valéria Aguiar (42) are relatively well off. They live on the outskirts, near Avenida Senador Teotônio Vilela, one of the major transport arteries leading to the circuit.

Swift Hands

Visitors outside the circuit gates are advised to keep their watches off, phones in their pockets, and maintain silence. Especially within the favela itself, vigilance is required due to nimble-fingered boys on every street corner.

Manoel Andrade and Valéria Aguiar pose on the roof of their home, with a distant view of the circuit.

For Manoel and Valéria, the events at the circuit are their primary, or indeed, their only source of income. They do not have paid jobs and do not aspire to have them. They rent rooms in their own house and in the houses of friends and acquaintances, both in the better and worse parts of the neighborhood. This suffices for a life that meets their standards, they emphasize.

Proudly, Manoel pulls out his phone. He shows a photo of Duca Borkovic, a Serbian race car driver with over 100,000 followers on Instagram. “He also rented something through me,” he says.

Armed Guard

At the beginning of their street, there is a permanent armed guard who keeps a close eye on what is happening. If he realizes that the people are trustworthy, he raises his arm in greeting. He is there purely as a precaution, Valéria assures later. “You have guards everywhere in São Paulo, especially in the expensive neighborhoods. Security gives us a sense of safety, but certainly our guests as well. This year we are fully booked. There are many Argentinians suddenly because of Franco Colapinto.”

She is referring to Williams driver Franco Colapinto, of course.

“No, the street guard hasn’t had to use his gun this week,” she says with a laugh. “In our experience, the dangers aren’t too severe. But that’s also because we live here and know where we should and shouldn’t go and what we should and shouldn’t do. We don’t get caught off guard easily. For tourists, it’s a different story. I know the stories of robberies from the news, but we’ve never had guests who’ve had unpleasant experiences.”

Around the annual F1 race, a dynamic ecosystem has emerged in Interlagos. Everyone tries to benefit in their own way, most of them legally.

Prostitution

“Of course, there are always some robberies around the circuit every year, and prostitution is rampant,” says guide and interpreter Alê Salvador. “But most people make money by renting out sleeping places and parking spaces or selling everything from water bottles to all sorts of unofficial F1 merchandise, ranging from caps to T-shirts. Homeowners with a rooftop terrace overlooking the F1 circuit are particularly fortunate these days.”

Manoel and Valéria are not avid followers of Formula 1, they emphasize. But they do realize that huge amounts of money are involved in the sport. “There is a lot of poverty here and the drivers are millionaires. That’s not fair,” Valéria believes, from the top floor of her house, where you can see the circuit in the distance.

First Tenants

At the same time, she is pleased with the annual visit of Formula 1, as she is with all other events at the circuit. Because it generates income. “For Formula 1, this starts 45 days before the race. That’s when we get the first tenants involved in setting up the event.”

Manoel also manages the rental of three apartments in the poorest part of the favela. He calls them Airbnbs, although he does not use that platform. He started renting out five years ago, when he still lived with his mother. “The house had two rooms. I would temporarily sleep in the room with my mother, and we rented out the other room.”

The difference in wealth with the street where he now lives, as the crow flies about 300 meters away, is significant. “That’s typical Brazilian,” he says. “The difference between rich and poor can sometimes be just one street. There is no social boundary here. I have friends and family in all parts of the favela. I live here, but work there,” he says, pointing to a part of the neighborhood where the houses or shacks are clearly in worse condition.

Ambiance and Conviviality

The recently re-elected mayor of São Paulo, Ricardo Nunes, lives just one and a half kilometers away, in an expensive villa district, adds Valéria. “They say he is working hard to stimulate this entire region. He is very popular because he comes from this neighborhood and brings events and thus money to Interlagos. And he is doing his best to improve the infrastructure in this area.”

She has lived in Interlagos since she was two. Moving to a more affluent part of São Paulo is not an option for her. She loves the neighborhood, despite all the social problems. “I live here with pleasure, feel happy. And I enjoy the ambiance and conviviality around Formula 1.” Manoel also remains loyal to Interlagos. “Why should I move? I live here, I work here. I don’t even have a car. My life is on foot. And the view is beautiful.”

He looks out from his rooftop terrace. In the distance, a Red Bull is driving on the track. Behind the wall, in another world.