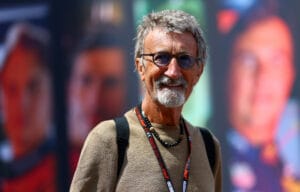

Formula 1 legend Eddie Jordan passed away in Cape Town on Thursday. With courage, perseverance, and a tremendous will to survive, the Irishman once established his own successful Formula 1 team. A portrait of a colourful and flamboyant go-getter.

‘How do you become a millionaire the fastest? By starting a Formula 1 team as a billionaire.’

This is a well-known joke, first introduced by Eddie Jordan. In the early nineties, when he was about to start a Formula 1 team, he contemplated the risks he was taking. He had 6.5 million euros in the bank, was happily married to Marie, and the father of four children. As a team owner, he was successful in Formula 3000, and he also made some extra money by managing a few drivers. Should he give all that up for an uncertain adventure in Formula 1? He already had a good life.

But that wasn’t enough for Jordan. The Irishman doesn’t like to play it safe and is always looking for new challenges. From the beginning of his career, he was known as a shrewd trader. In addition to his regular job (at the Bank of Ireland), he sold used cars, smoked salmon, and carpets – all to be able to race. First as a driver: through karts, Formula Ford, and the Irish Formula Atlantic championship, Jordan ended up in the British Formula 3 championship. With opponents like Andrea de Cesaris and Nigel Mansell, Jordan realized he would never be a top driver. The realization grew that Eddie Jordan Racing – the Formula 3 team he founded for himself in 1980, could no longer remain his private playground – he left the racing to more talented drivers.

Lack of Money as a Common Thread

At that time, Jordan had no money, and lack of funds would be a common thread throughout his activities. His financial need was so great in the early period that he fished car parts from other teams out of the trash to use for his own cars. Despite this – or perhaps because of it – Jordan decided to try his luck in the European Formula 3 championship. By contracting paying drivers, he managed to hang on and gradually even make some money. One of the first to embark on the adventure with Jordan was Dutchman Michael Bleekemolen. He also secured the team’s first podium at Zolder.

While Jordan primarily relies on paid drivers, he also keeps an eye out as a talent scout. Johnny Herbert, Martin Brundle, Jean Alesi, Eddie Irvine, Michael Schumacher, Heinz-Harald Frentzen: they have all driven for Jordan at some stage in their careers. In 1983, Jordan established EJM (Eddie Jordan Management). “If I wanted the best drivers, I initially had to invest in them myself to later, when they would grow into the top drivers I envisioned, earn my money back.” This is typical of Jordan, who sees a way to make money in everything.

This also explains why, after becoming the Formula 3000 champion in 1989, he considers making the switch to Formula 1. “That thought has always played in the back of my mind. A Jordan participating in Formula 1 is a dream come true. But it’s such a huge step. Buying a car from Ralt or Reynard is one thing. But to actually design a car on your own to then compete against teams like Ferrari and McLaren, is not something to take lightly.”

Jordan operates according to the philosophy of only moving to the next series after winning the title. At that time, Jordan had won more races in Formula 3 and Formula 3000 than all other British teams, so it’s a logical question he asks himself: what now? Continue on the well-trodden path and make good money. Or take risks and not only put that 6.5 million euros at stake but also his reputation and that of the sponsors and end up with a huge debt. However, setting up his own Formula 3 team has taught him a lot about the risks involved in such an endeavor. Jean Alesi then gives him the final push. Alesi regularly informs Jordan about the ins and outs at Tyrrel and concludes: “There’s nothing special that you can’t do!”

‘If it doesn’t work out, it doesn’t work out’

The final push to take the leap comes from the entrepreneurial Irishman’s wife, Marie. She knows that he will never be truly happy if he doesn’t try. “If it doesn’t work out, then it doesn’t work out. We started with nothing and if we end up with nothing, we’ll manage,” she tells her husband. After all, he is facing the biggest challenge of his life: how on earth do I build a car and who will design it?

In August 1990, the team name is changed from Eddie Jordan Racing to Jordan Grand Prix. Jordan signs a deal with Cosworth and Goodyear and the real work can begin. What Jordan and his companions are doing is, strictly speaking, madness; designer Gary Anderson and his team not only have to design, build and test the Formula 1 car, they are also responsible for the running of the Formula 3000 team. It’s also hard to imagine that no computers are used in the design of the Formula 1 car; the entire car is hand-drawn.

Once the car is ready and the first shakedown is over, the time comes to introduce the team to the general public. Only 29 journalists bother to come to the workshop in Silverstone to witness the unveiling of the Jordan-Ford 191, seated on plastic chairs. The press is impressed, but the skepticism remains: why go to all this trouble when the chance of failure is so high?

It is precisely this criticism that makes Jordan even more driven to prove himself. With success. He brings in 7UP, Fuji and Ireland as sponsors and secures Andrea de Cesaris and Bertrand Gachot as drivers. The first season is primarily a fight for survival. Not just financially, but also on the track. There are 34 drivers and only 26 starting places. This means that pre-qualifications are held. Teams that do not pass this qualification can leave immediately.

A Nightmare for Every Team Boss

A nightmare for every team boss, especially when there are sponsors as guests. Jordan has sleepless nights before the first race in Phoenix. Due to a gearbox problem, De Cesaris fails to qualify, but Gachot makes the grid. Jordan is overjoyed, he has been spared a humiliation. That the car also turns out to be competitive is something he had not dared to hope for. Gachot is in eighth place when his engine gives up six laps from the end. It’s a shame, but Jordan has made a good impression.

“After ten races, the team is sixth in the championship; the season is running smoothly. That is until Jordan is confronted with the fact that Gachot has to go to prison. The Luxembourger had gotten into a fight with a taxi driver in London in February of that year; in the heat of the battle, Gachot sprayed tear gas in the man’s face. He had never mentioned a word about it until a prison sentence was demanded against him. Suddenly, the team urgently needs to find a replacement driver. Jordan recalls a conversation with a representative from Mercedes, who was raving about a certain Michael Schumacher.

Jordan had seen Schumacher race before, but was not particularly impressed. “You could see he was good, but he wasn’t exceptional. Necessity breaks law, and so Jordan makes a phone deal with Wili Weber, the German driver’s manager. At Spa-Francorchamps, a circuit where the German has never raced before, Schumacher qualifies seventh. The fact that he doesn’t get past the first corner in the race due to a clutch problem is just a detail: a star is born.

Contract Signing

A week later, the signing of an official contract is on the agenda, but Mercedes and Schumacher and his representatives make such absurd demands that Jordan asks for an evening to think in order to come up with a counterproposal. The next morning at 10:00 UTC, Jordan receives a fax: ‘Dear Eddie, I’m very sorry but I am not going to be able to drive for your team. Best regards, Michael.’ Through the intervention of Bernie Ecclestone, Schumacher has signed for Benetton.

A valuable lesson for Jordan, who is beginning to understand the ways of Bernie Ecclestone better. “I had little money and Bernie had helped me a few times, but that also meant you had to swallow it when his methods worked against you.” Ron Dennis had welcomed Jordan earlier that year with the words: ‘Welcome to the Piranha Club’; now the team boss understood what was meant by it.

Jordan finishes his first season fifth in the constructors’ championship with 13 points. An unprecedented achievement for a team making its debut in Formula 1. But Eddie Jordan is far from satisfied. The financial situation of his racing team is so bad that it’s a close call whether the team has to be disbanded after a season. The following year, 1992, is one to quickly forget. Jordan scores one point and doesn’t get further than eleventh place in the championship. It’s the worst season in Jordan’s history, but at least the team has survived.”

On the Podium with Lewis Hamilton after the 2014 Spanish GP

In 1993, Eddie Jordan signed Rubens Barrichello. He also set his sights on another Brazilian: Ayrton Senna. Jordan caught the attention of the three-time world champion with an intriguing proposal. He offered Senna a two-year contract and 25 percent of the team. This share was to increase to 49 percent by the end of the second year. Jordan’s rationale was that the team’s value would increase so much with Senna’s arrival that his 51 percent share in the team would be worth more than the original 100 percent. Senna was interested, and several secret negotiations took place, but in the end, the Brazilian chose security and stayed with McLaren. The way he tried to lure Senna reflects Eddie Jordan’s mindset: creative and never afraid to step off the beaten path.

Team’s Progress and Challenges

With each season, the team improved. The relaxed rock ‘n’ roll atmosphere, the remarkable car decals (featuring the famous snake and hornet), and the provocative pit girls helped Jordan become a stable midfield player. The team regularly made it to the podium and won its first race in 1998 when Damon Hill kept his cool on a soaking wet Spa. This was a harbinger for 1999, which went down in the books as the best season in Jordan’s history.

However, doubt crept in before this could happen. Eddie had just turned fifty, was the sole owner of the team, and thus responsible for all debts and loans. He realized that if anything went wrong, he or – in the event something happened to him – his family would be burdened with a massive debt. “I wondered if I had gone completely mad,” he said. Eventually, Jordan sold 45 percent of the shares to investment bank Warburg Princus, restoring calm.

The Jordan 199

The Jordan 199 is the first car designed by the new Technical Director Mike Gasgoyne, although it is essentially a further development of the car drawn up by his predecessor Gary Anderson. The team employs several top talents such as Mark Smith, Sam Michael, and Dino Toso. Their first major success comes in Magny-Cours. Once again, it’s pouring rain; by gambling on a one-stop strategy, they control the race and Heinz-Harald Frentzen wins. With 26 points, Jordan suddenly ranks third in the World Championship. In Monza, Frentzen wins again and with only three races left and just ten points behind World Championship leaders Mika Hakkinen and Eddie Irvine, the German is suddenly a title contender. Despite immense pressure, Frentzen takes pole at the Nürburgring while his competitors falter. Frentzen’s chance to make a huge impact seems great as he comfortably leads, but it evaporates when the engine fails after his last stop. A silly mistake: the anti-stall must be manually turned off after each stop. Sam Michael reminds the driver of this after every stop, except this time – Frentzen forgets the procedure and the chance of victory goes up in smoke – along with the chance of the world title.

Disappointment and Challenges

The disappointment is great, but the team doesn’t give up. For the 2000 season, the goal is to at least match that third place. However, Jordan finishes in sixth place, which is seen as a major disappointment. Nevertheless, it’s not surprising that Jordan drops in the pecking order; Sauber receives factory support from BMW and Jaguar from Ford, running with customer engines becomes increasingly unusual and is clearly to the team’s disadvantage. But that’s not all. At the end of 2000, Mike Gasscoyne leaves for Renault, taking 29 staff members with him. Business partner Warburg Pincus, however, has full confidence in a new revival of Jordan and invests heavily. The team grows from 175 to 250 people, causing Eddie Jordan to lose control of his team. He is forced to delegate and increasingly feels that it is no longer ‘his’ team. In addition, the influence of manufacturers in Formula 1 grows with the arrival of Toyota and Formula 1 is affected by the aftermath of the September 11 attacks.

Financial Struggles and Future Plans

Jordan has hardly any long-term contracts with sponsors, making money a huge problem. At the start of 2003, Jordan has no choice but to cut his staff: of the 265 employees, 65 are laid off. During the same period, manufacturers threaten to start an independent championship under the GPWC flag. Manufacturers would then support private teams like Jordan and supply engines. The seriousness of the plans is evident from the fact that Mercedes makes a proposal for 2004. Jordan would then be called Jordan-Smart and provide a home for Mercedes test driver Gary Paffett. These remain wild plans, but the events do show where Jordan’s problem lies: without factory support, it becomes increasingly difficult for the team, not only to be successful, but also to survive.

Ecclestone as the Saving Angel

Partner Warburg Pincus sells its share package to Merrion Capital. The loss of his loyal partner prompts Jordan to consider selling his team. Jordan has become a backmarker. “I forced myself to look in the mirror and ask what the future of the team looked like and whether it was still possible to win,” says Jordan about that period. With the money-wasting newcomer Toyota, Honda that has taken over BAR, and BMW planning to buy Sauber, Jordan knows that the future for his team looks bleak. But selling a team is not that simple. Of course, there is interest, but no concrete plans are being made.

Until Bernie Ecclestone calls and asks Jordan to come to his office in London’s Knightsbridge. The big Formula 1 boss wants to save the sympathetic Jordan team from downfall and introduces the team boss to the Canadian Russian Alex Shnaider. Three days later, there is a deal: Jordan becomes MF1 Racing.

The deal gives Eddie Jordan a mix of relief and pride. “From the beginning of my motorsport career to the end, I have always remained independent. That was not always easy. But when you realize that to date there have only been five teams that have won multiple races over the past twenty years – including Jordan – I am extremely proud that I have succeeded. Especially because I did it as an independent man.”

After his career in Formula 1, Eddie Jordan enjoys a comfortable retirement. He spends a lot of time on his 17 million yacht and invests here and there in companies and shares. In 2005, he made ‘Eddie Jordan’s Bad Boy Racers’, a TV program about troubled youths whom he helps get back on track by teaching them the race mechanic profession. He was also chairman of the Rally of Ireland for some time and a F1 analyst for the BBC for several years. In recent years, he had a successful podcast Formula for Success, together with David Coulthard.

At the end of last year, Eddie Jordan announced that he was suffering from bladder and prostate cancer with metastases to his spine and pelvis. Jordan passed away on Thursday in Cape Town in the presence of his family. He was 76 years old.